A new theory of socioeconomic transformations. The fallacies of Marxism

Yuri K. Shestopaloff

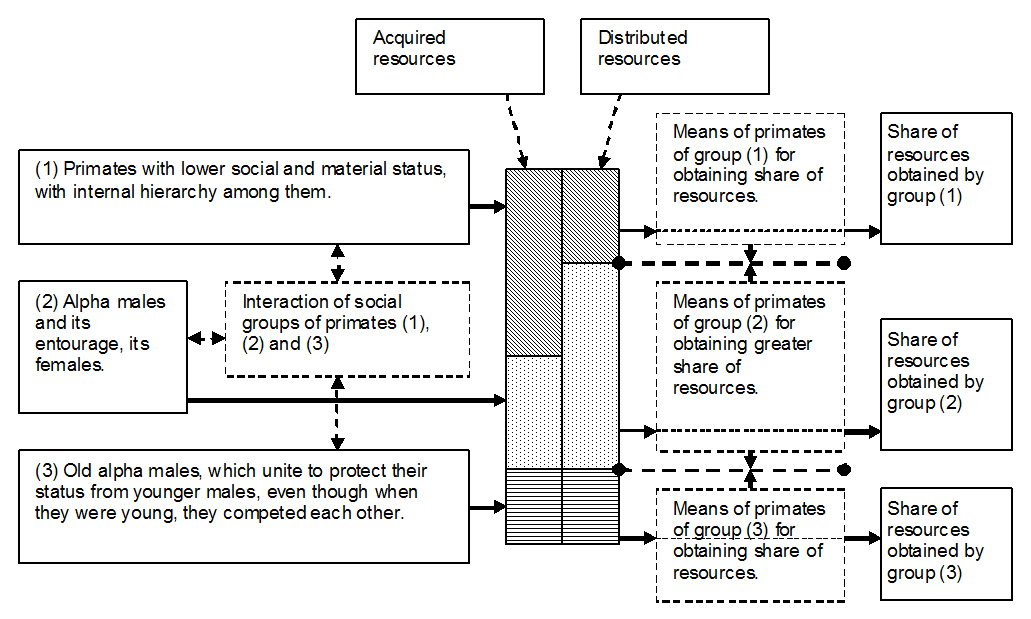

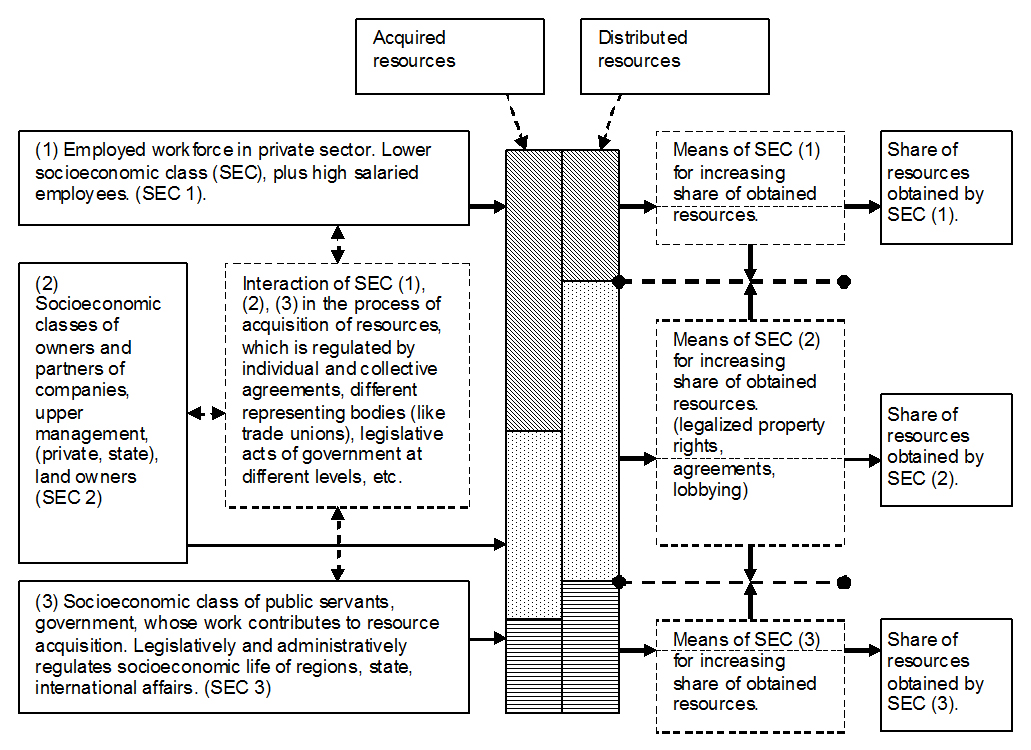

Fig. 2. Scheme of acquisition and distribution of resources by various socioeconomic classes (SEC). Bold dotted lines with bumps at the ends show the moving boundaries of resource allocations that the corresponding classes want to increase in its favor.